We all die from something. It’s a heart attack. A cancerous tumor. A car accident. Death may be sudden or drawn out after a long excruciating illness. At the end of every life, no matter how that end arrives, there is an infinitesimal moment of time that rests between death and life. It’s milliseconds before the last breath. It’s the final heartbeat.

Often, in that exact moment, we are alone. We die, and no one is there to bear witness, to give us permission, to tell us we were loved. There is no goodbye or last words. Death is usually a process one has to endure alone.

However, on rare occasions, one has the honor to be with someone as he dies. This week my mother and I attended to my step father, Rodney, as he moved through that time between life and death.

I met Rodney in 1987 when I was invited to meet a “friend” of my mother’s over dessert. A few days later I came home from school to find Rodney and my mother sitting on the living room couch. “Can we speak with you?”, she said. These are the words no teenager wants to hear. My mother asked me, in front of Rodney, if I minded if he moved in. Did I mind? Yes, of course I minded. Rodney was a stranger moving into our small two bedroom on East 72nd street. I said, “fine” and walked into my room and closed the door.

Over the course of the next 30 years I grew to love and understand Rodney. He started his tenure in our home as a stranger, but more like an alien. He had a heavy British accent. He sat around the house in dress slacks and a buttoned up oxford shirt just to read the newspaper. He wore shoes or slippers at all times, never letting his bare feet touch the floor. He used a fork and knife to eat everything. His laugh sounded like a near death experience. Anyone who has ever witnessed Rodney watching Jackie Mason knows what I mean.

If one could live solely on bacon and runny eggs, cookies, potato chips, chocolate and bread with gobs of butter, Rodney would have. That’s what he liked best and when my mother wasn’t around or looking, that’s exactly what he ate. He enjoyed heavy cream, Christmas pudding with brandy butter and foie gras. He loathed onions and garlic and knew without a doubt if they were used in any dish. Many, many, a meal was sent back in a restaurant due to an errant scallion.

Rodney believed every problem could at least be minimized by having a chocolate. Once when I received my first speeding ticket on my way home from college he offered me what he thought was a box of chocolates. The wrapped box he received as a gift had been in the freezer for no one knows how long. The chocolates turned out to be a picture frame. We had a laugh. I didn’t get my chocolate that time but it made me feel better all the same.

With Rodney came family we barely knew across an ocean. Over the years our families blended in unforeseen ways, and the word step felt less like an insult and more of a matter of order. When Rodney greeted you or said goodbye he planted a kiss on your cheek like it was going to be his last. He held your head with two hands and lingered with his lips pressed to your cheek. He did this to men and women, to the old and the children, to family and friends. It was his way of transmitting his love when there may not have been words for his affections.

Rodney was obsessed with cars, drivable as well as model ones. He drove like a maniac let loose from the Indy 500. Rodney spent hours wearing magnifying head gear hunched over his desk putting together remote-controlled models from hundreds of pieces. Painstakingly, he painted the cars to look exactly like their real counterparts. These cars were his prized possessions, and he barely shared them.

When my son, Emmett, was born my husband and I decided to give our boy the Hebrew name of Rodney’s father. This was a man I never met but it didn’t matter. The honor was for Rodney and so Emmett became known at his bris at Nissan Wolf (Wolf for Rodney’s dad). Rodney loved all of his grandchildren. But with Emmett he shared a love of birds, animals and nature.

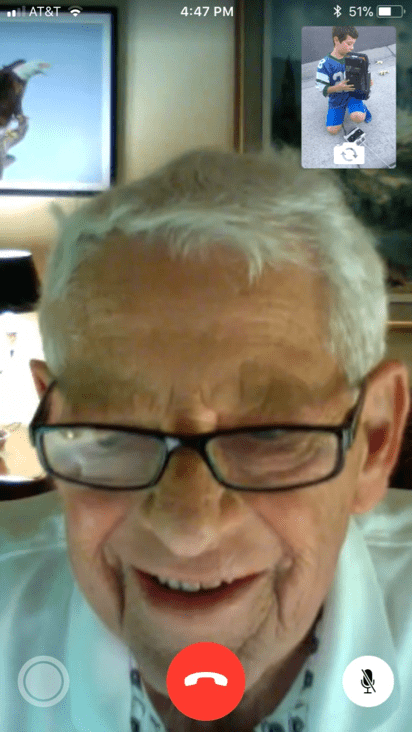

This October, just before my Emmett’s 11th birthday, a box arrived. Rodney had meticulously packed up two of his special remote-controlled cars that he built decades ago and sent them to Emmett. This was a bittersweet gift. I knew Rodney was too sick to enjoy these cars, and yet, this was a gift of extreme love. We Facetimed with Rodney so he could tell Emmett how to set up his cars. Emmett immediately loved his gift as any 11-year-old boy would. But he didn’t know it would be the final one from this grandpa. Somehow, I did.

A few weeks later my mother texted. Rodney was in the hospital with pneumonia. They were moving house that same day. It was terrible timing, and she needed help. I texted, “I can come this weekend.” My mom texted back, “I wish you were here now.” So I booked the next redeye and arrived on Halloween. I unpacked my mother and Rodney’s house while my mom went back and forth to the hospital. One moment it seemed Rodney was doing a little bit better. The next he was slipping away.

After years of two kinds of cancer and a debilitating neck complication Rodney was weak. He had reached the limits of his will, and he made the decision that he no longer wanted to live. When I arrived at his bedside in the ICU Rodney was awake but worn out and in pain. Shortly after 8am on November 2nd Rodney said declaratively with full competence, “I want to die.” No more intervention. No more treatment. He told my mother he loved her as he always did. She told Rodney that she loved him. Not long after that Rodney slept, never to fully wake again.

By 12pm the Rabbi came to sing the Shema to Rodney and give him his last blessing. If a moment can be dreadfully sad and simultaneously comforting, this was it.

Just before 1pm Rodney’s daughter Louise called from England and spoke a loving last message to Rodney she composed with her sister, Victoria. We held the phone to his ear and although he was sleeping his brow moved. He heard the message, I’m sure of it.

At 1:30pm Rodney was settled into the hospice unit in the hospital. It was warm and peaceful in that room. All of the wires and tubes that monitored Rodney were removed. His horrific neck brace that pained my mother to see as much as Rodney to wear was discarded.

Rodney’s son-in law Jonathan sent a beautiful text message. My mother read it aloud to Rodney.

Rodney’s long lost but recently found daughter Jayne called and whispered yet another message in Rodney’s ear.

My mother and I told Rodney it was ok if he was ready. My mother said, “I love you darling. It’s ok to go.” She held his hand and gave him kisses.

He took a breath and then nothing. A moment hung in the air. Was it the last breath? But then Rodney breathed again. This happened several times. The nurse said this was the end. She left the room and closed the door silently leaving my mother and me with Rodney.

My mother whispered words to Rodney. I stood at her back.

We bore witness.

We gave him permission to end his own suffering.

We said I love you.

We said goodbye.

And then a breath. And then nothing.

The nurse confirmed that Rodney died. There was a peacefulness in that moment that was unexpected. Rodney’s death was dignified, on his own terms, painless, quick and with his beloved wife by his side. I don’t know that one could ask for more in that infinitesimal moment between life and death.

There’s a Jewish phrase people share when a loved one dies.

May his memory be a blessing.

I never understood that saying until recently. How could a memory of a loved one who died be a blessing? Wouldn’t it be better if that person was alive and not a memory? Wouldn’t that be the blessing?

Not always. Rodney was in a lot of pain. It would have been wonderful if he could live on with health and happiness. But that wasn’t his story. He lived a full life with love, family, good friends, adventure and passion. He made mistakes and had flaws. But in the final hours of his life, none of that mattered. He went in peace, and that was truly a blessing.

We all die. And often there is pain. There are words unsaid. There are loose ends and unfinished business. When a memory becomes a blessing it means that one can move past the unsaid and the suffering. It means that the memory of a dead relative brings more joy and smiles than sadness. In Rodney’s case the time between the pain and the blessing of his memory seems incredibly short. Seeing him take his very last breath, knowing there was peace, comfort and love wipes away a great deal of pain.

May his memory be a blessing.

Thank you. It already is.